Pangilinan, Michael R. M. [Siuala ding Meangubie]. (2012). An introduction to Kulitan, the indigenous Kapampangan script. Angeles City: Center for Kapampangan Studies. ISBN 978-971-0546-23-7.

It is probably safe to say that the Philippines today is a state whose citizens are confused about their identity, ignorant of their history and unmindful of their heritage. Despite the advancement in archaeology and scholarly research into her pre-colonial past, the average student still learns in class that Philippine history began only with the coming of the Europeans in the early 16th century. This implies that the people of these islands would never have become part of the ‘civilized world’ had it not been ‘discovered’ by Western adventurers, namely by the Portuguese explorer Fernão de Magalhães who ‘discovered’ these islands for Spain in 1521. It is no surprise then why the average citizen of these islands proudly wears the brand of a 16th century foreign monarch in whose name his ancestors were tyrannized and his country raped and plundered for more than three hundred years. Philippines and Filipino are alien words that hold no indigenous significance in any of the ethnic languages of the archipelago. They are names derived from Philip II, the 16th century Spanish king.

These non-native names, Philippines and Filipino, have for generations now been used to promote a new form of colonialism among the indigenous inhabitants of this archipelago (Martinez, 2004; DILA, 2007). By law, the term Filipino now stands for the nationality, citizenship and national language of all the ethnolinguistic groups within these islands (Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, 1987). Since then, all the indigenous languages and cultures of the various ethnolinguistic groups within the archipelago have been politically reduced to the status of mere “regional dialects”. They are now being sacrificed and pushed to the brink of extinction in the name of a contrived “national” unity. To be Filipino is to speak Filipino, which is actually just another form of the Tagalog language in a clever disguise. In reality, Filipino nationalism is just an alternative word for Manila-Tagalog Imperialism. National unity is a convenient excuse to a new form of non-violent ethnic cleansing (Mantawe, 1998; Avila, 2007; DILA, 2007 and Dacudao, pers. comm., 2012 April 13-15). How Tagalog became synonymous to Filipino is discussed in detail in the community website of the Save Our Languages Through Federalism Foundation, Inc. (SOLFED) and Defenders of the Indigenous Languages of the Archipelago (DILA), and in the book Filipino is NOT Our Language published by DILA in 2007.

Figure 1. The Kingdom of Luzon (呂宋國) as it appears on a Japanese map during the Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644). From “A look at history based on Ming dynasty maps” (從大明坤輿萬國圖看歷史) posted by zhaijia1987 in Baidu Tieba (百度贴吧) on 2010 November 11.

Long before the idea of a Filipino nation was even conceived, the Kapampangan, Butuanon, Tausug, Magindanau, Hiligaynon, Sugbuanon, Waray, Iloko, Sambal and many other ethnolinguistic groups within the archipelago, already existed as bangsâ or nations in their own right. Many of these nations formed their own states and principalities centuries before the Spaniards created the Philippines in the late 16th century. The oldest of these states include Butuan (蒲端) which existed on Chinese records as early as 1001 C.E., Sulu (蘇祿) in 1368 C.E. and the Kingdom of Luzon (呂宋国) in 1373 C.E. These three sovereign states were ruled by kings (國王) and not by chieftains according to Chinese historical records (Zhang, 1617; Scott 1984; Wang 1989; Wade, 2005 and Wang, 2008).

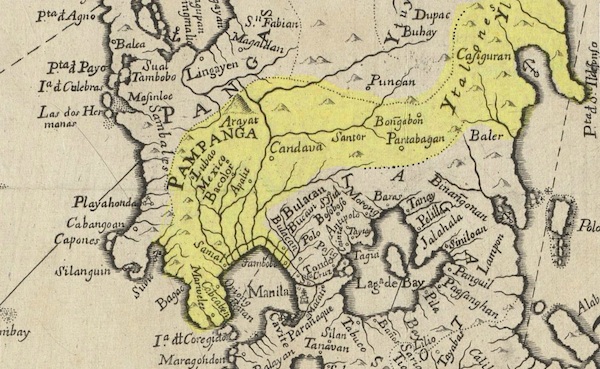

Figure 2. Map of Pampanga from Pedro Murillo Velarde’s 1744 Mapa de las Islas Filipinas. The Pampanga Delta Region had been inaccurately assigned to Bulacan.

The Kapampangan nation was once a part of the Kingdom of Luzon [Fig. 1]. They were one of the Luçoes, ‘people of Luzon’, encountered by Portuguese explorers during their initial ventures into Southeast Asia in the early 16th century (Scott, 1994). The Kapampangan homeland, Indûng Kapampángan (Pampanga), became the first province carved out of the Kingdom of Luzon when the Spaniards conquered it in 1571 C.E. (Cavada, 1876 and Henson, 1965). Indûng Kapampángan’s political boundaries once encompassed a large portion of the central plains of Luzon, stretching from the eastern coastline of the Bataan Peninsula in the Southwest, all the way to Casiguran Bay in the Northeast (Murillo Velarde, 1744; San Antonio, 1744; Beyer, 1918; Henson, 1965; Larkin, 1972 and Tayag, 1985) [Fig 2.]. It was said to be the most populated region in Luzon at that time, with an established agricultural base that can support a huge population (Loarca, 1583; San Agustin, 1699; Mallat, 1846; B&R, 1905; Henson, 1965 and Larkin, 1972). It also has a highly advanced material culture where Chinese porcelain is used extensively and where firearms and bronze cannons were manufactured (Morga, 1609; Mas, 1843; B&R, 1905; Beyer, 1947; Larkin, 1972; Santiago, 1990b and Dizon, 1999). The old capital of the Kingdom of Luzon, Tondo (東都: “Eastern Capital”), once spoke one language with the rest of Indûng Kapampángan that is different from the language spoken in Manila (Loarca, 1583; B&R, 1905 and Tayag, 1985). Jose Villa Panganiban, the former commissioner of the Institute of National Language, once thought the Pasig River that divides Tondo and Manila to be the same dividing line between Kapampangan and Tagalog (Tayag, 1985). The descendants of the old rulers of the Kingdom of Luzon, namely those of Salalílâ, Lakandúlâ and Suliman, can still be found all over Indûng Kapampángan (Beyer, 1918; Beyer, 1943; Henson, 1965 and Santiago, 1990a).

![Figure 3. A typical brown-glazed four-eared Luzon jar (呂宋壷 [褐釉四耳壷]) exported to Japan by the Kingdom of Luzon in the mid-16th century. Photo courtesy of Hikone Castle Museum (彦根城博物館) Newsletter, Vol. 13, 1991 May 1.](http://siuala.com/wp-content/uploads/Luzon-Jar-Hikone-Museum-600.png)

Figure 3. A typical brown-glazed four-eared Luzon jar (呂宋壷 [褐釉四耳壷]) exported to Japan by the Kingdom of Luzon in the mid-16th century. Photo courtesy of Hikone Castle Museum (彦根城博物館) Newsletter, Vol. 13, 1991 May 1.

If the Kapampangan nation made up the bulk of the population of the Kingdom of Luzon, then perhaps the oldest evidence of Kapampangan writing can be found in the jars (呂宋壺) exported to Japan prior to the arrival of the Spaniards in the 16th century C.E. [Fig. 3]. In his book Tokiko (陶器考) or “Investigations of Pottery” published in 1853 C.E., Tauchi Yonesaburo (田内米三郎) presents several jars marked with the ruson koku ji (呂宋國字) or the “writing of the Kingdom of Luzon” (Tauchi [田内], 1853 and Cole, 1912). The marks that looked like the Chinese character ting (丁) found in several Luzon jars might have been the indigenous Kapampangan script la (), the first syllable in the name “Luzon” [Fig. 4].

Writing has always been a testament to civilization among the great nations. The Chinese write ‘civilization’ as wénmíng (文明) or ‘enlightenment through writing’, combining the characters wén (文) ‘writing’ and míng (明) ‘brightness’. Sadly, the Kapampangan nation, a once proud civilization with a long established literature has now become a tribe of confused barbarians. Although many Kapampangans can read and write fluently in foreign languages, namely Filipino and English, they are strangely illiterate in their own native Kapampangan language.

Figure 4. A page in Faye-Cooper Cole’s English translation of Tauchi Yonesaburo’s Tokiko (陶器考) showing the ‘national writing of Luzon’ (呂宋國字) in comparison to Philippine scripts.

The Kapampangan language currently does not possess a standard written orthography. The dispute on which orthography to use when writing the Kapampangan language in the Latin Script ~ whether to retain the old Spanish style orthography a.k.a. Súlat Bacúlud or implement the indigenized Súlat Wáwâ which replaced the Q and C with the letter K, remains unsettled. This unending battle on orthography has taken its toll on the development of Kapampangan literature and the literacy of the Kapampangan speaking majority (Pangilinan, 2006a and 2009b). No written masterpiece that could rival the works of the Kapampangan literary giants of the late 19th and early 20th centuries has yet been written. The few poems that earned a number of contemporary poets the title of Poet Laureate no longer have the same impact that would immortalize them in the people’s collective memory. Worse, the Kapampangan language is now even showing signs of decay and endangerment (Del Corro, 2000 and Pangilinan, 2009b).

While the old literary elite continue to bicker endlessly which Latinized attitudinal procedure to follow, a small yet growing number of Kapampangan youth have become frustrated and disillusioned with the current state of Kapampangan language and culture. They see the old Spanish style orthography that still uses the letters C & Q as a perpetuation of Spain’s hold into the intellectual expressions of the Kapampangan people. The new orthography that has replaced the letters C and Q with K is also viewed to be foreign since they identify it with the Tagalog abakada. Instead of being forced to choose which orthography to use in writing Kapampangan, they chose to forego the use of the Latin script altogether. They decided instead to go back to writing in the indigenous Súlat Kapampángan or Kulitan.

References:

Avila, Bobit. (2007 August 24). Ethnic cleansing our own Filipino brethren? In The Philippine Star. Retrieved 2012 March 16 from http://www.philstar.com/Article.aspx?articleId=15037.

Beyer, Henry Otley. (1918). Ethnography of the Pampangan People: A Comprehensive Collection of Original Sources. Vol. 1& 2. Manila, Philippines. [Microfilm].

Beyer, Henry Otley. (1943). A Brief History of Fort Santiago. Manila (no publisher).

Cavada, Agustin de la. (1876). Historia geográfica, geológica y estadistica de Filipinas. 2 vols. Manila: Ramirez y Giraudier.

Cole, Fay–Cooper. (1912) Chinese Pottery in the Philippines. Field Museum of Natural History Anthropological Series,Vol. 12 (1), Chicago.

Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines (1987). In Chan Robles Virtual Law Library. Retrieved June 6, 2009 from http://www.chanrobles.com/article14language.htm.

Defenders of the Indigenous Languages of the Archipelago (DILA). (2007). Filipino is not our language. Angeles City, Pampanga: Defenders of the Indigenous Languages of the Archipelago (DILA).

Del Corro, Anicia. (2000). Language Endangerment and Bible Translation. Malaga, Spain: Universal Bible Society Triennial Translation Workshop.

Dizon, Eusebio et al. (5 October 1999). Southeast Asian Protohistoric Archaeology at Porac, Pampanga, Central Luzon, Philippines. Mid-Year Progress Report. Archaeological Studies Program. University of the Philippines at Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines.

Henson, Mariano A. (1965). The Province of Pampanga and Its Towns: A.D. 1300-1965. 4th ed. revised. Angeles City: Mariano A. Henson.

Larkin, John A. (1972). The Pampangans: Colonial Society in a Philippine Province. 1993 Philippine Edition. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Loarca, Miguel de. (1583) Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas. In E. Blair and J. Robertson, eds. and trans. The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898, volume 5, page 34 – 187.

Mallat, Jean. (1846). Les Philippines: histoire, geographie, mœurs, agriculture, industrie, commerce des colonies Espagnoles dans l’Oceanie. Paris: Arthus Bertrand. [English ed. 1998] Santillan, P. and Castrence, L. (Transl.), Manila: National Historical Institute.

Mantawe, Herb. (1998). Ethnic Cleansing in the Philippines. [2012 March 11 ed.]. Retrieved March 23, 2012 from http://dila.ph/ethnic.pdf.

Martinez, David C. (2004). A Country of Our Own: Partitioning the Philippines. Los Angeles, California, USA: Bisaya Books.

Mas, Sinibaldo de (1843). Informe sobre el estado de las Islas Filipinas en 1842. Madrid. Vol 1.

Morga, Antonio de. (1609) Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas. Obra publicada en Mejico el año de 1609 nuevamente sacada a luz y anotada por Jose Rizal y precedida de un prologo del Prof. Fernando Blumentritt, Impresion al offset de la Edicion Anotada por Rizal, Paris 1890. [Reprinted 1991] Manila, Philippines: National Historical Institute.

Murillo Velarde, Pedro. (1744). Mapa de las islas Filipinas. In The Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Pangilinan, Michael R.M. (2006a) Kapampángan or Capampáñgan: Settling the Dispute on the Kapampángan Romanized Orthography. A paper presented at the 10th International Conference on Austronesian Linguistiics, Puerto Princesa, Palawan, Philippines. January 2006.

Pangilinan, Michael R.M. (2009b). Kapampangan lexical borrowing from Tagalog: endangerment rather than enrichment. A paper presented at the 11th International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, June 21 – 25, 2009, Aussois, France.

San Agustin, Gaspar de. (1699). Conquistas de las Islas Philipinas 1565-1615. [1998 Bilingual Ed.: Spanish & English] Translated by Luis Antonio Mañeru. Published by Pedro Galende, OSA: Intramuros, Manila.

San Antonio, Juan Francisco de. (1738-1744). Cronicas de la apostolic provincial de S. Gregorio de religiosos de n.s.p. San Francisco en las islas Philipinas, China, Japon. Sampaloc: Juan del Sotillo.

Santiago, Luciano P.R. (1990a) The Houses of Lakandula, Matanda, and Soliman [1571-1898]: Genealogy and Group Identity. In Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, Vol. 18, No. 1.

Scott, William Henry. (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Scott, William Henry. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Tauchi Yonesaburo (田内米三郎). (1853). Toukikou (陶器考: Investigations of Pottery). See English Translation in Cole, Fay–Cooper. (1912).

Tayag, Katoks (Renato). (1985). The Vanishing Pampango Nation. Recollections & Digressions. Escolta, Manila: Philnabank Club c/o Philippine National Bank.

Wang, Teh-Ming (王徳明). (1989). Sino Suluan Historical Relations in Ancient Texts. (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, 2001). Unpublished typescript.

Wang, Zhenping. (2008). Reading Song-Ming Records on the Pre-colonial History of the Philippines. 東アジア文化交渉研究 創刊号. [Higashi Ajia bunka kōshō kenkyū, No.1] (2008): 249-260.

Wade, Geoff. [tr.] (2005) Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu: an open access resource. Singapore: Asia Research Institute and the Singapore E-Press, National University of Singapore: http://epress.nus.edu.sg/msl/place/1062

Zhang Xie (張燮). (1617). Dong Xi Yang Gao [東西洋考] (A study of the Eastern and Western Oceans). http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/directory/sumita/5A-161/index.html, Volume (分冊) 3:9.

© Copyright 2012 Siuálâ Ding Meángûbié

![Pangilinan, Michael R. M. [Siuala ding Meangubie]. (2012). An introduction to Kulitan, the indigenous Kapampangan script. Angeles City: Center for Kapampangan Studies. ISBN 978-971-0546-23-7.](http://siuala.com/wp-content/uploads/184001_4490404499711_1283281000_n.jpg)